“Even if the body deteriorates, the heart stays the same”

We often hear about dedicated people, and let ourselves be admired and motivated by them. In modern times, one can possibly say that there is a significant difference between true dedication and assumed dedication. This has probably always been the case. But due to the pressure from appearing perfect on social media, a strong factor is that you want to appear somewhat more dedicated than you really are. Especially among younger people, one can imagine. We take a look at someone one fore sure can call dedicated – and the most interesting things: how they mindset make this happen. Kaihōgyō 回峰行 ( “circling the mountain” ) The 1000 days challenge..

The article contains: #Have I really sacrificed anything, #Quest for enlightenment, #The marathon monks #The focus is all about present #In the end

Have I really sacrificed anything

Being a trainer and coach, I’v heard more than one time: “I deserve “this” or “that”, because I’ve sacrificed so much! And to be honest, I have for sure tough similar things myself. But have I really done so much? Have I really sacrificed anything that make me deserve something more than others? Taking these questions, and honestly let them sink in.. well that might not feel so comfy. The most of us probably have tough that we deserve something – and we all do, but is it in balance with what we have put down? That said, the most of us also grow past that stage of claiming that we deserve thing more than others – if our moral compass is more or less straight – and specially if we are leaning towards the aspect of Budo.

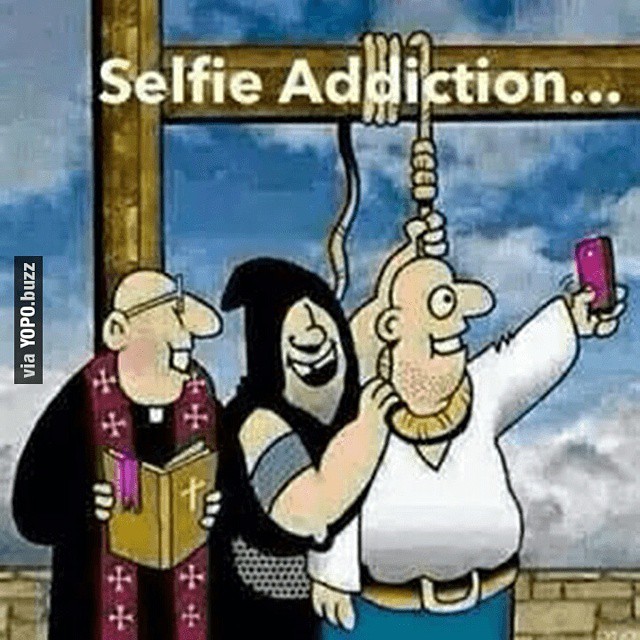

But in today’s world – could you attend to a great camp, or a tournament, without posting one single picture in the social media about you participating? Do you feel that it is a important part of it, to get a picture together with the instructor? Well, it is nice to have some memories, and nice pictures of it and especially with some good friends. But, we have touched the topic..

Quest for enlightenment

Part of Tendai Buddhism’s teaching is that enlightenment can be attained in the current life. The kaihōgyō (回峰行) (“circling the mountain”) is an ascetic practice performed by Tendai Buddhist monks. The practice involves walking a route on Mount Hiei (the location of the Tendai school headquarters), the longest of which takes 1000 days to complete; all the while offering prayers at halls, shrines and other sacred places. According to the Tendai monks, you can only achieve enlightenment in your current life through extreme self-denial and they achieve this by taking up the Kaihogyo quest. Due to this, the monks are often referred to as the “Marathon Monks”

The marathon monks

The marathon monks of Mount Hiei follow the learning that through the process of selfless service and devotion that this can be achieved, and the kaihōgyō is seen as the ultimate expression of this desire – enlightenment can be attained in the current life.

- During year 1, for 100 straight days, the monk runs 30 km (about 18 miles) per day.

- During the 2nd year, the monk runs another 30 km every day for 100 straight days

- During the 3rd year, the monk runs the same miles per day for another 100 straight days.

- During the 4th year, the monk runs 30 km every day but for 200 straight days this time.

- During the 5th year, the monk runs another 30 km per day for another 200 days straight. After completing this, the monk goes for 9 consecutive days with no food, rest or water. Two monks stand guard to ensure he doesn’t fall asleep.

- During the 6th year, the monk runs 60 km per day (approximately 37 miles) for 100 straight days.

- During the 7th year, the monk runs 84 km per day (about 52 miles) for another 100 straight days. During the final 100 days, he must run for 30 km per day.

During the first 100 running days, a monk can withdraw from the quest but after that, there’s no withdrawal- the monk either completes the quest or kills himself. For this latter clause, the monk has with him a lengthy rope and short sword during the journey, at all times.

The focus is all about present

The monks lives isolated, with the mountains and forest close. No tourism is allowed, nor are there any disruptive elements such as laptops, cell phones or Facebook that will disturb their focus.

Too often, we pursue our goals half-halfheartedly. We leave too much room to escape commitment, and fail to create negative consequences for inaction. Often make little progress or we in the matter of fact just quit. Seen from a monk’s perspective, he will reach his goal, or take his life if he fails. Then there is no doubt that the focus will be on something other than what one can normally imagine. Would we kill yourself if we failed Shodan? Of course we would not done that.. and of course deep down inside we also know that we can get another try “next year” And there it lays – “another try” knowing that you only have one shot, will sharpen things significant. So if we set this in between “taking our life” and “try next year” what could we said? If I fail the test I will never train again. If you really love this – that would be quite some pressure. It is just one thing about that: you become the person that quit. In our game we say never give up – it is the same a the monks, but there is a big gap in between anyway.

For the monks, the focus is all about present. Not on the future, or the goal that’s lays ahead – and newer dwells about the past. Focusing on the process in front of you – like a fighter on the Tatami. Don’t think about the final of the tournament in your first fight, focus on the fight and the challenge it brings – could this be a parallel? I think so.

In the end

The marathon monks of Mount Hiei are so real as it gets. And it is all from inspiring, to frighting – and hard to understand how dedicated a human being can be. To make the goal just a part of a greater purpose, gives an idea about a wide perspective. The toughs around this, and drawing a parallel into the Kyokushin part, are just one person mind here and now. In the end it is all about to have and open mind – not so open that your “brain fall out” but a wide perspective do also need an anchor, a weight that keeps you steady in your course, in search of your goal.

SH